EXPLORE NAMIBIA’S NAMIB SAND SEA with this slideshow, check the location map and get all the facts and information below.

For slideshow description see right or scroll down (mobile). Click to view slideshow

Location and Values: The Namib Sand Sea lies at the heart of the Namib, a coastal fog desert on Africa’s South Atlantic coast in Namibia. It is a vast area of spectacular sand dunes, featuring two super-imposed systems – an ancient (semi-consolidated) one below, with an active one above. Remarkably, the sand itself originates thousands of kilometres away in the headwaters of southern Africa’s major rivers, from where it has been transported by the forces of erosion and river flow into the ocean, then picked up and brought back onshore by strong ocean currents. Once onshore it is blown by the wind and piled up in a spectacular diversity of formations, determined at each location by the interaction of onshore and offshore winds as well as the influence of inflowing seasonal rivers and occasional flood events. The world heritage site – one of the biggest in Africa – falls within the Namib-Naukluft Park, where access is very limited as there are few roads in the vicinity.

The Namib is an extremely dry desert, but it supports a remarkable diversity of unique plants and animals that have evolved special adaptations to enable them to live in this extraordinarily hostile environment. In particular, many species have developed ways of trapping the atmospheric water that comes ashore as fog, so they can survive without rain. And they have evolved special ways of living in the ever-changing dunes, ‘swimming’ and ‘diving’ into the sub-surface sand to escape the scorching heat and the risk of predation.

REVIEW OF WORLD HERITAGE VALUES: The specific attributes which qualify the Namib Sand Sea for world heritage status can be summarised as follows:

-

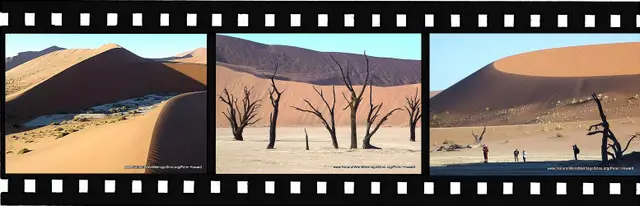

Massive dunes at Sossusvlei in the Namib Sand Sea world heritage site (Namibia)

World’s only coastal desert with extensive dune fields influenced by fog. The Namib Sand Sea (NSS) is primarily composed of two dune systems, an ancient (semi-consolidated) one overlain by a younger active one. The dune fields make up 84% of the world heritage site, with the remainder composed of a variety of other geomorphic features including gravel plains and gramadullas (8%), coastal pans/flats (4%), rocky hills at the fringes (3%), inselbergs within the sand sea (1%), a coastal lagoon, endorheaic pans, ephemeral rivers and rocky shores. The outstanding attributes of the sand seas are derived from interactions between the land, the ocean and the atmosphere. Strong winds from various directions, linked to rain and fog, have an overriding influence on the area and define its key attributes.

- Massive dunes made of sand transported from afar. Unlike most of the world’s dune fields (which are derived from local bedrock in situ), the Namib dunes are derived from material transported from afar. Sand is carried to the area from the interior of southern Africa by river, ocean current and wind. This three-part ‘conveyor system’ begins with erosion of material in the headwaters of the Orange River which is carried into the South Atlantic, where it is picked up and driven northwards by strong ocean currents. Deposited as beach sand it is then mobilised and transported inland by wind where it creates the diversified aeolian desert landforms and features of the Namib Sand Sea.

- Diversity of dune formations. Sixteen distinctive dune types are recognized across the three main zones of the sand sea, with transverse dunes in the coastal strip, linear dunes in the centre and star dune systems in the east. This diversity of dune formations creates a spectacular dunescape with a unique interplay of shape, colour, movement and habitat.

-

The desert-adapted Palmatogecko is one of the unique animals of the Namib Sand Sea

Plant and animal adaptations to desert conditions. Plant and animal communities are continuously adapting to life in the hyper arid environment. Fog serves as the primary source of water and this is harvested in extraordinary ways while the ever-mobile wind-blown dunes provide an unusual substrate in which well-oxygenated subsurface sand offers respite and escape for ‘swimming’ and ‘diving’ invertebrates, reptiles and mammals. The outstanding combination and characteristics of the physical environment – loose sand, variable winds and fog gradients across the property – creates an ever-changing variety of micro-habitats and ecological niches that is globally unique on such a scale.

- Rare and endemic species, particularly invertebrates. Although the sand sea habitat exhibits relatively low levels of overall species richness, certain taxa of the sand sea fauna and flora show high levels of endemism. Eight species of plant (53% of the sand sea total), 37 arachnids (84%), 108 insects (52%), 8 reptiles (44%), a bird (11%) and two mammals (17%) are known only from Namib sand sea habitats.

CONSERVATION STATUS AND PROSPECTS: The nature of the Namib Sand Sea – a vast inaccessible area of fog-bathed desert dunes – makes it sufficiently inhospitable to deter most forms of exploration or exploitation. There are virtually no roads or facilities of any kind within the world heritage site. Although there were some early pioneer efforts to exploit limited deposits of alluvial diamonds along the coastal plains in the early part of the 20th century, this proved uneconomic and any remaining mineral prospecting licenses were cancelled at the time the world heritage site was inscribed in 2013. Today the area is protected within the Namib Naukluft Park, with some limited use of desert plants and animals around the fringes of the property by indigenous communities and a growing tourism industry. The most significant management challenges are regulating visitor activities in the few accessible parts of the site, controlling alien plants (especially along the seasonal rivers) and managing local community access rights. Water resources require careful management if the few seasonal rivers that penetrate the area are going to be maintained, but the key values of the site seem secure.

MANAGEMENT EFFECTIVENESS: The majority of this vast uninhabited desert survives in a largely undisturbed state due to the extreme prevailing conditions and difficulty of access. The few areas that are readily accessible are located close to the edge of the site where visitor accommodation (and most critically, water) can be provided. So, despite very low levels of management intervention the unique ecological values of the site remain largely intact and pristine. Management of tourism, especially around Sossusvlei and the Sesriem area (where three quarters of the park’s visitors are concentrated) presents some challenges, and there is a need to enhance management capacity and visitor management in this area particularly.

REVIEW OF CONSERVATION ISSUES AND THREATS: The following issues represent specific threats to the ecology, conservation and values of the Namib Sand Sea world heritage site.

Park entrance gate at Sossusvlei. While tourism brings economic benefits to the Namib Sand Sea

Disturbance from tourism. Although the nature of the terrain across most of the property limits access by visitors there are some potentially damaging impacts of tourism. These are already being experienced in some areas and include off-road driving, noise pollution from low-flying sight-seeing aircraft, litter and sanitation problems, unauthorised camping, overcrowding and disturbance of critical wildlife habitat (e.g. notably a vulture breeding colony). The demands of tourism are growing rapidly and present levels of management input (financial and staffing) are barely adequate to address these demands. There is a need for a more strategic approach to tourism planning to disperse visitor use (e.g. away from the Sossusvlei area), improve basic infrastructure at heavily-used sites and enhance the visitor experience with better interpretation and education facilities.

Members of the indigenous Topnaar community live in scattered villages along the Kuiseb River valley. People from these villages make use of resources from within the Namib Sand Sea as they have done for centuries.

Hunting, fishing and resource use by local communities. The Topnaar community, now living in scattered villages along the Kuiseb River valley (which marks the northern boundary of the world heritage site), claim ancestral rights to land and resources within the area. They maintain a limited number of livestock (mainly cattle and goats) which are grazed along the northern fringes of the site, and harvest other renewable natural resources for subsistence use (notably the wild !Nara melon fruits). They are given a limited hunting quota for animals that are shot by government staff for distribution of meat between community members. Topnaar community resource use rights are not formally recognised and although present levels of off-take and management practices may be within sustainable limits there is a need to reach a formal agreement on traditional use of resources.

Invasive alien species. There are some invasive plants and animals, including 11 species of plants, one fish, two birds, two mammals and 12 invertebrate species (as noted in the world heritage nomination dossier). Most of the invasive plants are carried into the property by ephemeral rivers and are difficult to eliminate due to regular re-infestation during each flooding cycle.

Sandwich Harbour RAMSAR site is a wetland of international importance for waterfowl which lies within the Namib Sand Sea world heriage site and could be threatened by water abstraction from the Kuiseb River valley.

Water extraction. In a country as dry as Namibia water resources have special significance and there is a real possibility that any surface water and subterranean aquifers associated with the world heritage site will be used, with unknown ecological consequences. In particular the ephemeral rivers which arise in the western escarpment and drain into the site (or along its borders) are threatened by the possibility of upstream impoundments. Furthermore, extraction of subterranean water supplies from the Kuiseb River valley (which is already happening on a significant scale to supply the nearby town of Walvis Bay) may alter the ecology of the Ramsar-designated wetlands at Sandwich Harbour (as well as other attributes of the site). These potential threats need to be explicitly recognised and developments that are likely to impact the world heritage site must be subject to rigorous Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and mitigation procedures.

Mining and mineral exploitation. Although there are no active mining operations within the world heritage site, diamond mining has been undertaken in the coastal zone periodically since the early 1900s and some abandoned infrastructure remains to this day. Substantial discoveries of uranium have been made in recent years on gravel plains north of the world heritage site but the prospects for significant new finds of diamonds, uranium or other minerals within the area are considered limited. In recognition of this, the Government of Namibia passed a landmark decision in February 2012 (after submission of the nomination dossier) to cease all prospecting within the area and terminate all Prospecting Licenses.

Links:

Google Earth

Official UNESCO Site Details

Birdlife IBA

World Heritage Outlook

Gobabeb Training and Research Centre

Slideshow description

The slideshow provides a comprehensive overview of Namibia’s Namib Sand Sea world heritage site, showing the area’s spectacular desert and coastal landscapes, wildlife habitats, endemic reptiles, insects and other threatened animals and plants. It highlights some of the conservation management issues, and illustrates local community livelihoods and some of the facilities and typical visitor experiences.

The slideshow begins with photos from one of the most spectacular parts of the Namib, at Sossusvlei. This is a visitor ‘hotspot’, attracting more visitors than any other area, and with good reason. The dune formations on either side of the (usually) dry riverbed here are particularly tall and spectacular. Access is relatively easy on a tarmac road and there are a range of accommodation options nearby. One of the most photographed sites in this area is Dead Vlei, where the gaunt skeletons of camel-thorn trees that grew here 900 years ago stand in a white-clay pan, surrounded by tall red dunes. The slideshow continues with views of the eastern (coastal) part of the site where there are some important coastal wetlands at Sandwich Bay (a designated RAMSAR site). Some of the most remarkable desert-adapted species of animals and plants are shown, including a side-winding adder, fog-collecting beetle, desert-adapted oryx antelope, chameleon and web-footed Palmatogecko. One of the most important desert plants, as a food source for members of the indigenous Topnaar community, is the thorny !Nara melon. The slideshow is completed with a series of aerial photographs showing the range of dune formations and geological features in some of the less accessible parts of the world heritage site.

Factfile

Website Category: Deserts

Area: 30,777 km2

Inscribed: 2013

Criteria:

- (vii) natural beauty,

- (viii) geological,

- (ix) ecological process,

- (x) biodiversity